Q: Is policing too generalized at supervisory level and too specialized at the operational level?

I'm not one (1) to shy away from discussions about generalism vs specialism in policing. Heck, I start many of them!

So when Liam Mahon posed this question, I knew I'd need more space than tweets:

My thoughts:Here’s one to consider:— Mahoo (@SystemsNinja) March 10, 2019

Is policing too generalised at Management level and too specialised at the delivery level?

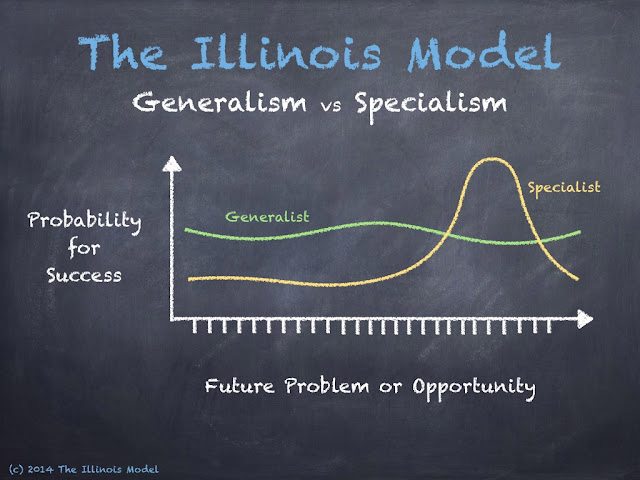

Supervisory (management) levels should be more generalized than those below. Operational (delivery) levels should be more specialized than those above.

Generalists are those who make connections and jump specialties. They are the bull sharks who can swim in fresh and salt waters. They coordinate the complex work of multiple, diverse specialists by seeing relationships and forecasting implications that a narrow-minded specialist cannot.

Specialists have deep expertise in a narrow context or set of circumstances. They understand the complicatedness of the situation...as long as they have education, understanding, or experience in those particular situations.

Is policing too generalized at supervisory level and too specialized at the operational level?

Trick question - because it's relative to some optimal, idealized level.

Policing would become more optimal if we could match up specialists with real problems, challenges, and situations in the field. As a supervisor, I'd be remiss if I withheld specialized resources for a known or highly predictable problem. However, I might also be over-confident in my awareness, appreciation, and nuance of the problem, challenge or situation. I might simply send in the wrong people with the wrong skills to deal with something for which they are ill-suited.

Bosses should be generalists. I can't appreciate most of the arguments for specialized supervisors. Disagreements will likely arise at the perspective of scope - as to high up the hierarchy we are talking. Does this mean there should be no supervisors of a juvenile sex crimes detective team? No, but at some point, there needs to be a more generalized boss of that boss.

The problem with matching up problems with specialists is that policing and emergency response more broadly (emergency/trauma medicine as another), is not that predictable. We need to push out generalists to probe the environment. But these generalists should be empowered to identify, stabilize, (or stabilize then identify...I'm not sure which), and then pass the situations off to specialists. Generalists holding onto specialized problems does not produce the best outcomes. This holds for both generalist/specialist theory...and what I've experienced in real life practice.

But this also comes down to "good enough." I don't need to call out a traffic crash reconstructionist for a fender bender.

In that example, maybe we need to address which types of situations demand excellence...and which simply just need to be satisfied to a point where they go away. That's an issue that brings great discomfort to those who demand the best and seek excellence.

We have to keep in mind that excellence comes at a cost. And frankly, sometimes the cost is too high.

In summary: Generalists rule in uncertainty. Specialists rule when their skills match up with the future. Luck plays a significant, but uncomfortable role in this.

***

Lou Hayes, Jr. is a criminal investigations & intelligence unit supervisor in a suburban Chicago police department. With a passion for training, he studies human performance & decision-making, creativity, emotional intelligence, and adaptability. Follow Lou on Twitter at @LouHayesJr or on LinkedIn. He also maintains a LinkedIn page for The Illinois Model.

Comments

Post a Comment