Teams versus Groups

I played team sports most of my childhood and early adulthood: baseball; basketball; volleyball; men's slow-pitch; rugby.

As a police officer, I also gravitate towards teams: SWAT; training cadres; investigative task forces.

But though reflection, I question whether some of these teams were actually groups.

I anticipate this post will draw criticism for my language. My intention is to share differences in concept and principle, more than selling anyone on distinct labels of Team or Group. Stick with me, and offer more appropriate terminology rather than beating me over the head with your dictionary.

My kids are on a swim team. However, there is really no "team" aspect to swimming; it's a collection of individual swimmers. Team scores are merely a summation of individual points. Even for relay teams, it's one (1) swimmer at a time. Swim teams, and even relay teams, are plug-and-play; it's quite easy to swap out individuals. This is because a swim team lacks interaction or interplay between members. Sure they motivate, inspire, and root for each other, but performance is quite individual.

Simply, I'd prefer if they called it a swim group.

Groups are collective and modular. Members are recruited and trained to perform in controlled conditions towards a unified goal or mission. The work is divisible. Members are specialized, assigned, and matched up with isolated functions. The roles are not only defined, but there's a replicability or replace-ability of each member. The interactions between members are predictable, known, mechanical, routine, choreographed, or systematic. Groups are managed, with a certain element of efficiency.

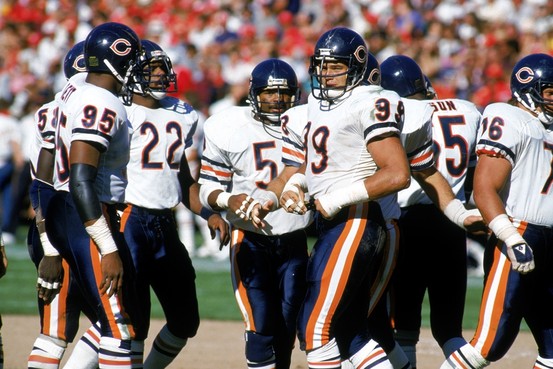

It'd be much easier for a baseball "team" to swap out a right-fielder (or any other position!) than for a rugby team to swap out an inside center. (No sweat fellow Americans... I've included a positional chart.)

Teams, on the other hand, rely upon elements of self-organization, purpose, and values. The connections between members is their strength. The working environment is more complex, less predictable, more evolutionary, more organic. Team members rely less upon choreography and more on synthesizing on-the-fly. They appreciate the nuances, tacit knowledge, and the inarticulables within the team. Because of high interplay and low standardization, when team members are swapped out, there is a steep learning curve from both old and new members in this new team.

Consider a crowd assembled around a fresh accident site. A problem, challenge, or situation suddenly emerged and strangers come together to help. A successful ad-hoc team here will take but a few moments to figure out who is best suited to render medical aid (Nurse! Doctor!), who can do the heavy lifting (the strong guy), and who can telephone or run for emergency responders.

I maintain a close group of friends from Catholic prep school. Thirty (30) years later, there are still no agendas, no schedules, no projects, no supervisors. Social events emerge. Weddings and funerals come and go. Weekend trips happen. In most all senses of the terms above, this is a team of friends.

Consider the collections of people of which you are a part.

How replaceable are you? Him? Her? How quickly could you get up-and-running if someone went missing? I've been on both of ends of that phone call: "Hey, we need someone for our softball game tonight. Can you play?"

Or is your collection of people something unique and special? Do you finish each others' sentences? Can you read your teammates' minds? How naturally do you shift roles, morph, adapt, and flex for the new situation at hand?

The good and obvious news is that no one (1) has to pick...and absent context, neither is better. All fall onto a spectrum bookended by Team and Group...or some other more appropriate labels.

I find the value of discussing the differences between Teams and Groups in how we recruit members, develop them, impose policy, establish hierarchies, and design systems, interfaces, controls, and procedures.

Or how we leave those things up to those actually doing the work, and adapting them based on their current situation.

***

Lou Hayes, Jr. is a criminal investigations & intelligence unit supervisor in a suburban Chicago police department. With a passion for training, he studies human performance & decision-making, creativity, emotional intelligence, and adaptability. Follow Lou on Twitter at @LouHayesJr or on LinkedIn. He also maintains a LinkedIn page for The Illinois Model.

Comments

Post a Comment